—by Mary Lou Egan

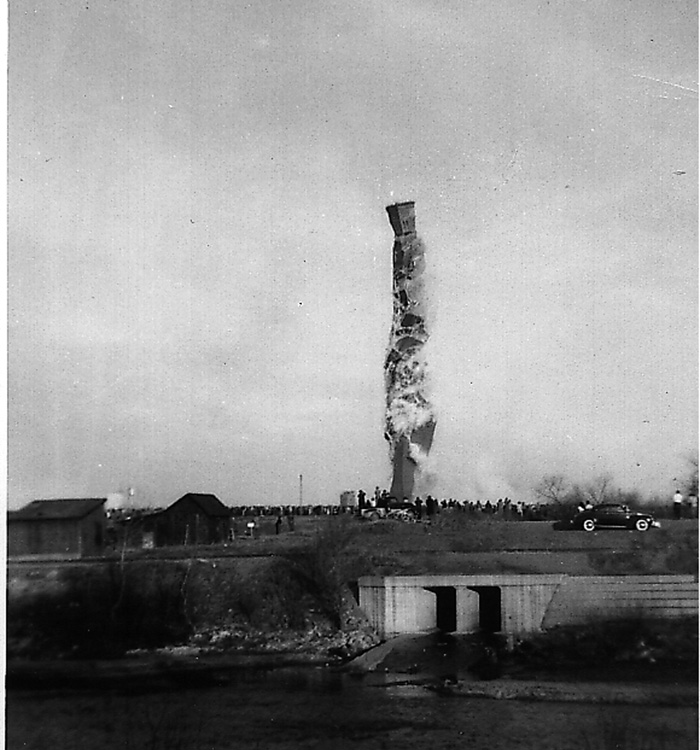

The story and photos occupied several pages of both the Denver Post and the Rocky Mountain News. KOA Radio carried the broadcast live and a score of airplanes flew overhead. An estimated 100,000 people gathered near the site while an additional 250,000 watched the event from rooftoops and ridges all over the city. The occasion was the demolition of the Grant Smelter smokestack, a 350-foot remnant of Denver’s glory days of mining and smelting.

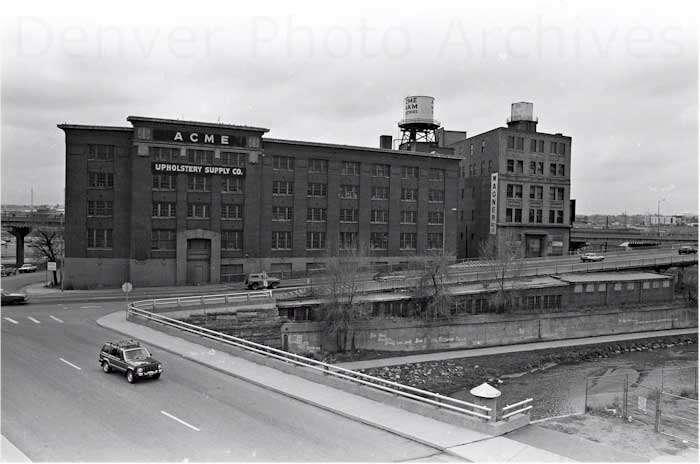

The giant chimney had been built in 1892 as part of an expansion of the Omaha and Grant, Denver’s largest smelter. It was the tallest structure in the region and a symbol of a time when smelting was the city’s largest industry.

A year after the completion of the stack, the nation experienced a depression that hit mining and smelting hard. Changes in technology, the depletion of rich ores and labor unrest brought the halcyon days of smelting to an end. The Omaha and Grant Smelter closed in 1903 and was gradually dismantled, until only the enormous smokestack remained. Neighborhood children used the stack as their private playground, riding their bicycles in and out, and daring each other to climb its steep walls. Retired fireman Ed Westerkamp was one of those kids. “We used to play around that old Grant Smelter stack.

There were a couple of ponds there and hills we could ride our bikes up and down.”

Various economic proposals for the giant chimney were made over the years, including its use as an incinerator for the city’s refuse. There were arguments for its preservation as well as for its demolition, but, in the end, issues of safety and economics won the day.

Sunday, February 26, 1950, was the day selected for the demolition. Officials and spectators began arriving at the site at 9 am and listened to speeches as preparations were finalized. The Denver Post eulogized the stack, “From its mighty mouth. . .spewed the smoke from rich ores that flowed through its smelter by the millions of tons.” Mayor Quigg Newton added, “I think we’re all sorry to see the stack go, but it was one of those things that had to be done.”

The crowd remained patient through delay after delay. Finally, at 5:00pm, Fred “Tombstone” Backus, a veteran powder man, turned over the detonator to Thomas Campbell, Manager of Improvements.

A second later a series of five blasts, each two seconds apart, exploded in the base of the 7,000-ton tower. This was the moment when the stack was expected to fall westward into a dump area. Nothing. It took three more blasts and “a million bricks crashed to earth and a blinding cloud of cement and dust enveloped the officials and spectators.” Half of the tower remained standing. Seventeen minutes later, as people were examining the damage, there was a rumble and another section suddenly collapsed. It would take more dynamite on the following day to finish the job.

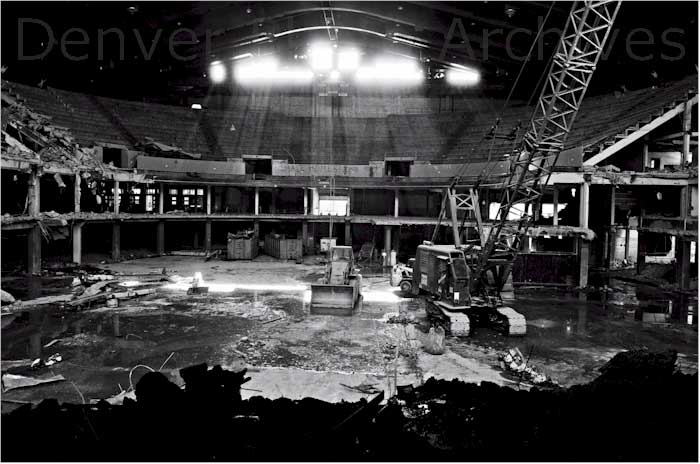

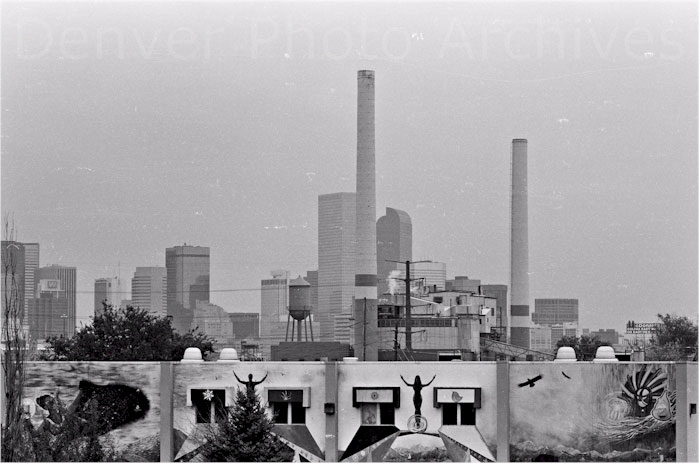

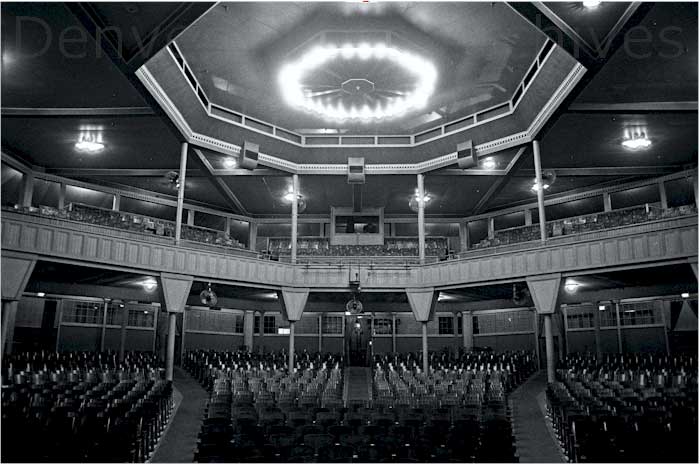

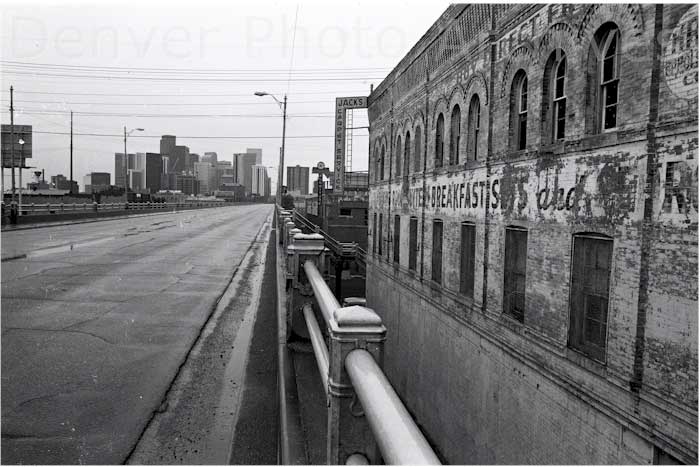

Denver was pleased with itself for shedding its frontier image. The city was growing, with a modern interstate highway and sleek new buildings changing the downtown skyline. The city’s newest addition, completed and dedicated in 1952, would be the Denver Coliseum, replacing the smelter stack, a crumbling symbol of Denver’s industrial past.

B50 Note: Mary Lou Egan is a professional graphic designer and watercolor artist who also enjoys history and preservation, and writes and maintains the Globevillestory blog. Photos of stack courtesy of Janet Wagner. Photo of coliseum courtesy of Ian Denny.