—by Jennifer Boone

After 25 years of retail I decided to make a midlife change of profession. My husband and I sold our business with lofty notions of re-entering the art world after a long hiatus and of contributing in some new, creative way to our north Denver neighborhood. But with recession knocking at the door, and our resources being sucked dry by our children’s college fees, it became evident that a career decision must be made sooner rather than later. In a moment considerably lacking in creativity, I decided to go to real estate school.

After 25 years of retail I decided to make a midlife change of profession. My husband and I sold our business with lofty notions of re-entering the art world after a long hiatus and of contributing in some new, creative way to our north Denver neighborhood. But with recession knocking at the door, and our resources being sucked dry by our children’s college fees, it became evident that a career decision must be made sooner rather than later. In a moment considerably lacking in creativity, I decided to go to real estate school.

In class, while lecturing about the various forms of real estate ownership, the instructor taught us about housing cooperatives – noting that there never were any co-op’s in the Denver area. ‘Au contraire,’ I thought to myself, as I had personally been born into a Denver housing co-op located, ironically, three blocks or so from the Kaplan Real Estate School.

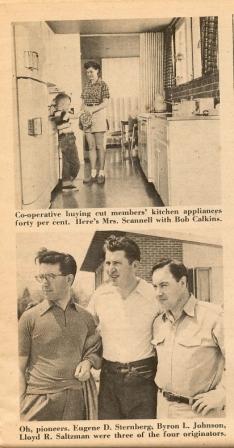

Amid the independent, western culture of Denver in the late 1940’s Mile High Housing Association began as an idea shared by several University of Denver professors who sought an affordable housing alternative so they might move their growing families out of the tiny Quonset huts and Butler units that then served as DU faculty housing. Among the organizers were Byron Johnson (an economics professor and future Colorado U.S. Representative), Eugene Link (sociology), Lloyd Saltzman (marketing and sales), and my father, Eugene Sternberg, a modernist architect and professor in the new School of Architecture and Planning at DU. My father became the senior architect and project manager for the group.

In 1950, with limited resources (approximately $100 per family), the building committee embarked on a mission to find 10+ acres where my father would design a community of modest homes ranging in size from 800-1500 sq ft. A down payment was made on an alfalfa field located behind Bethesda Sanatorium (now Denver Academy) and ground was broken on the project April, 1950. (At that time the developed portion of Colorado Boulevard virtually ended at Alameda)  On this site 32 houses were built at an average cost of $12,000 per unit. Mile High Housing would become the first cooperative of single family homes in the nation to be built under new federal housing legislation for cooperative housing that authorized FHA to insure generous loans at 4% interest for a period of 40 years. According to my father, this legislation made it possible for poorly-paid university professors to afford housing of their own.

On this site 32 houses were built at an average cost of $12,000 per unit. Mile High Housing would become the first cooperative of single family homes in the nation to be built under new federal housing legislation for cooperative housing that authorized FHA to insure generous loans at 4% interest for a period of 40 years. According to my father, this legislation made it possible for poorly-paid university professors to afford housing of their own.

Eugene Sternberg was a passionate Czech architect educated at University in Prague and Cambridge University in England. My mother, Barbara Edwards, studied sociology at the London School of Economics. Early in their relationship, in their respective fields, they both served on the re-planning project of Milton, a small village northeast of Cambridge. This collaboration of social concerns and architecture was a springboard for the creative life they would share in America. In a memoir written by my mother and father for the private enjoyment of our family (entitled “Our Lives and Families”), Eugene explained how Mile High Housing encompassed their ideals of socially conscious architecture:

The physical design of Mile High Housing expressed, in concrete terms, my philosophy about housing. I felt strongly that houses were like people, they needed neighbors. I always preferred to design communities rather than single homes. Here I managed to put into practice some contemporary site design. The layout took care of the needs of the people who lived there for safety and intimacy.

Mile High was one of my father’s first opportunities to gain practical experience with building code regulations, material costs and American contractors. The general contractor for the project was a light-hearted fellow with a sense of humor. My Czech father, still very much a foreigner, could not yet comprehend nor appreciate subtle, American sarcasm. When the first fireplace was built Eugene noticed the damper screw had been installed in the middle on the front of the fireplace wall, facing the living room. The drawings called for the screw to be discreetly placed on the side wall, facing the dining room. In our family book my father described the scene:

“Bill, that screw has got to be facing the dining room.” A number of the brick layers stopped working and listened to the discussion. “Gene,” said Bill with a straight face, “I don’t care where you screw. I prefer the living room.” I had no idea what he was talking about. This contractor was questioning my design! “The screw will be according to my specifications,” I shouted. The discussion went on in this vein for some time. The workmen roared with laughter and I just didn’t get it.

In planning the street layout Eugene used a loop design, which discouraged through traffic, unlike the usual grid most American cities were built on. Curved streets also would slow traffic and enhance safety, but he had to fight for approval of the subdivision plan. “Firemen,” said the Fire Chief, “are like horses with blinders on. If you present them with a curve, they will miss the fire.” The Arapahoe County Commissioners also objected to the narrow 20 ft width of the road. They refused to grant a permit for the project until the architect gave them a personal guarantee that if any community members objected to the road width, he would widen it at his own expense. So my father gave them this guarantee in writing.

In planning the street layout Eugene used a loop design, which discouraged through traffic, unlike the usual grid most American cities were built on. Curved streets also would slow traffic and enhance safety, but he had to fight for approval of the subdivision plan. “Firemen,” said the Fire Chief, “are like horses with blinders on. If you present them with a curve, they will miss the fire.” The Arapahoe County Commissioners also objected to the narrow 20 ft width of the road. They refused to grant a permit for the project until the architect gave them a personal guarantee that if any community members objected to the road width, he would widen it at his own expense. So my father gave them this guarantee in writing.

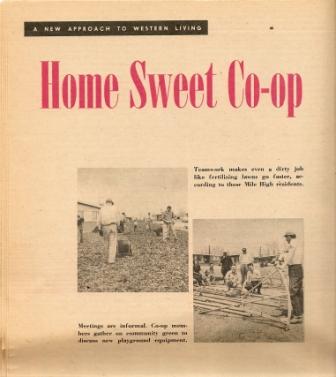

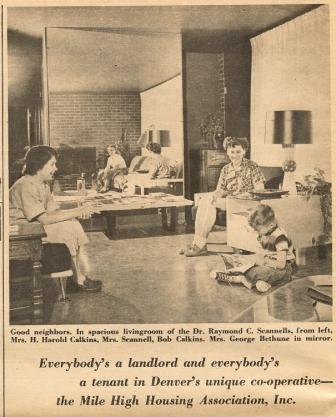

The circular lane of Mile High surrounded a central two-acre “village green” complete with playground equipment and a small, open air amphitheater for neighborhood gatherings (built with salvaged brick by volunteer DU architectural students). The post-war baby boom ensured that our community was brimming with children. For a child Mile High was a delightful, close-knit, community-rich environment in which to grow up. Holiday celebrations were often shared and many included a children’s parade around our little circle.

Despite the fact that families were quite large family in the 50s and 60s most Americans lived in homes less than 1500 sq ft. My father died in 2005 before the onset of today’s recession and the stark reality that faces us as a result of our collective excesses. Eugene was an idealist and as such he embraced, with fervor, the American freedom to choose ones own destiny and surroundings. He especially enjoyed and revered the western culture of individualism; he had a great admiration for the cowboy, so much so that he donned western shirts and refused to wear a tie for the last 30 years of his life. However, the values of the west often times ran counter to some of his fundamental beliefs about good urban design and the importance of community.

Despite the fact that families were quite large family in the 50s and 60s most Americans lived in homes less than 1500 sq ft. My father died in 2005 before the onset of today’s recession and the stark reality that faces us as a result of our collective excesses. Eugene was an idealist and as such he embraced, with fervor, the American freedom to choose ones own destiny and surroundings. He especially enjoyed and revered the western culture of individualism; he had a great admiration for the cowboy, so much so that he donned western shirts and refused to wear a tie for the last 30 years of his life. However, the values of the west often times ran counter to some of his fundamental beliefs about good urban design and the importance of community.

Sternberg had a life-long interest in designing affordable housing, and he contributed to many such housing projects and developments during his career. Sternberg’s modernist style was accompanied by a perfectionist’s eye, and a strong social ethic. He opposed zoning that separated people of different classes or ethnicities, and he spoke outwardly about the way dwindling natural resources would force people to change the way they live and work. (Denver Public Library, Western History Department, Sternberg Biography)

In the 1980s members of the Mile High Housing Cooperative celebrated the paying off of their 40-year mortgage by burning it, an event documented by a Rocky Mountain News article entitled “South Dahlia co-op burns FHA mortgage ahead of schedule.” In 1989 the members dissolved the cooperative model and exchanged their co-op shares for warranty deeds and private ownership. They reincorporated into South Dahlia Lane Community (SDLC). Today the community remains a quiet enclave, tucked away aside the sprawling I-25 corridor.

In a sense my real estate school teacher was correct; housing co-ops never really caught on in the west, although a newer version based on a Scandinavian model and called co-housing is making progress in Colorado. Perhaps in the new economy there will be a renewed interest in housing that is affordable and offers a more modest lifestyle; housing built on a human scale that is sensitive to it’s surroundings and that has evolved beyond the ‘bigger is better’ model of the last several decades. Today’s housing market offers an opportunity for us to restore a balance lost and return to the notion of creating homes and neighborhoods, not primarily for profit, but also for the enjoyment of the occupants and for the communities they create.

B50 Note: Jennifer Boone lives in Denver with her husband Casey; both are Denver natives. Recently she’s been helping research, format and prepare her mother’s manuscript on Anne Evans who was an early contributor to Denver’s cultural institutions: Denver Art Museum, Denver Public Library, Civic Center Park (and its sculptures) and Central City Opera. Pictures were scanned from Empire, the Magazine of the Denver Post; Voice of the Rocky Mountain Empire: June 22, 1952.

Jennifer, thank you so much for writing this article! Your parents have contributed so much to our community and we can all learn a lot about social responsibility from their efforts.

The good news from the real estate market is that the trend for the past few years has been moving toward good design and modest square footage. Hopefully developers are finally getting that message and will stop eviscerating existing neighborhoods or the beauty of undeveloped land with their McMansions and high-density housing.

Jennifer,

You mention that the Sternberg home plans were made available by Better Homes and Gardens for $25. Do you have any information on how to get an original copy of such plans or any back issues of Better Homes and Gardens that would feature the plans or the general Usonian styles? We have recently moved into a home whose original owner bought the plans. We have his revised blueprints (the original handwritten prints) and we have several Better Homes and Gardens supplemental catalogs listing “optional” items for the homes. The owner has various items circled and you can tell he just loved the home.

We have become quite infatuated with the story of our home, studying Frank Lloyd Wright’s influence and the other architects that developed liveable neighborhoods. Any information you might be able to provide would be appreciated!

Thanks,

Nicole Coleman

Nicole,

At this time I have no idea whether the Sternberg plans are somehow still obtainable through Better Homes and Gardens. I suggest you contact BH&G directly and inquire about archived materials dating back to the early 50s. You might also check in the Western History Dept of the Denver Public Library. I am presently in the process of cataloging my father’s papers, including many magazine articles, house plans, etc. I will keep an eye open for the BH&G plans and let you know if any surface.

For further quick study of Denver modernist neighborhoods you might enjoy “The Arapahoe Acres Historic District” by Diane Wray, published by Historic Denver, Inc. as part of the Historic Denver Guides series. This guide provides a driving tour of the neighborhood and an accurate account of its history including Eugene Sternberg’s contributions. Also of interest is Mile Hi Modern (milehimodern.com), a Kentwood City Properties Real Estate Team, whose website provides a nice overview of other modern homes and enclaves and a driving tour of Krisana Park and Lynwood.

This was such a great read. I’m doing research on co-ops’ practicality in Denver so this was a great read to come across. Thank you! In the last 6 years, do you think with the market strengthening so much, something like a co-op would thrive in the Denver market?