— By Victoria Tupper Kirby

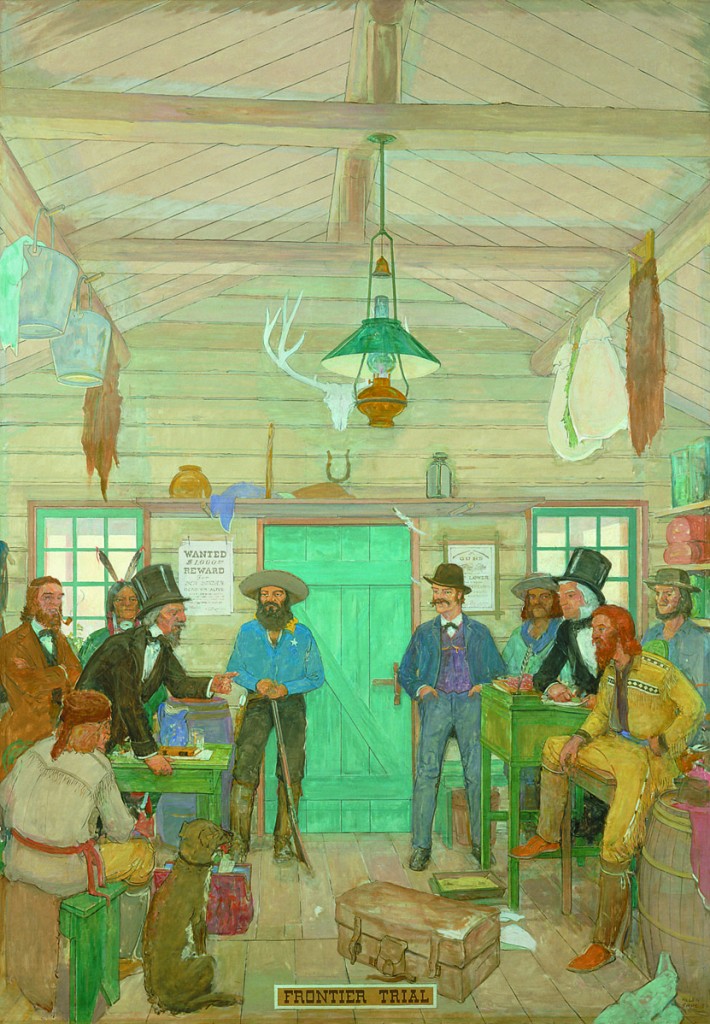

Frontier Trial, by Allen Tupper True. Photo credit: Marcia Ward, Imagemaker; courtesy of Victoria Tupper Kirby

As early as the 1920s, there were plans to have Denver muralist Allen Tupper True decorate the courts in the City and County Building in Denver. Five judges of the District Court signed an affidavit dated September 14, 1920, that approved the services of True to “assume charge of and furnish the appropriate decorations for the new Criminal Court Building, including the two court rooms therein contained.”

In 1931, there is a record of his proposal for six murals there for which he was to be paid $15,000. There was controversy about the number of murals and payment, which seems to have slowed up the project.

According to the April 9, 1949, edition of the Rocky Mountain News, the judges of the district were again to consider a request, this time by “of a group of civic leaders” for True to paint murals in offices of the court clerks.

In the April 13, 1949, issue of the Denver Post, Richard Dudman reported, “An intramural controversy was brewing Wednesday in the Denver city hall. Quick reaction came from three sources to the awarding of $6,000 commission Tuesday to Allen T. True, Denver artist, to paint two murals in the offices of the clerks of the Denver district and county clerks.” The article reported that one judge wanted to approve the mural before it was installed. The chairman of the Denver art commission said his commission must approve them and an artist complained that there was no open competition. Dudman speculated that a “taxpayer’s suit” might arise.

In an article in the Rocky Mountain Herald dated April 23, 1949, Colorado’s Poet Laureate Thomas Ferril wrote, “I think it is shameful, this petty little rumpus somebody has churned up as to whether Allen True should paint courtroom murals in the City and County building. Denver has a genius for cultural cat-and-dog fights. Allen True is a distinguished American artist. It’s all wrong.”

An agreement finally was signed June 10, 1949, “by and between the District Judges sitting in and for the Second Judicial District of the State of Colorado, parties to the first part, and ALLEN TRUE, of the City and County of Denver, Colorado . . . to paint a mural decoration [Miner’s Court and Frontier Trial] approximately eight feet four inches by twelve feet” in the rooms occupied by the Clerk of the District Court and the Clerk of the County Court “for a total sum of $6,000.” The contact mentioned that the two sketches had been approved by the mayor, the Municipal Art Commission, and the Honorable C.E. Kettering, judge of the County Court of Denver.

Oh, how slowly the gears of government grind.

True began work on the two murals at his Raleigh Street studio in Denver.

After the contract was signed and the bickering at an end, the following article appeared in the Denver Post: “Workmen will begin Monday to prepare the walls in the offices of the clerks of the District and County Courts to receive murals painted by Allen T. True, Denver artist. Mr. True was commissioned to paint a mural for the District Court and another for the County Court of scenes depicting early Colorado justice.

The first will be hung in County Court. It is a mural of the old circuit rider, a frontier judge who rode on horseback dispensing justice in various towns in the circuit. The County Court mural will show the circuit rider holding court in a barn. The one which will hang in the District Court is called Miner’s Court and [will] show court being held beside a sluice box. . . . Mr. True will receive $6,000 for his work.”

Commenting on these murals, Lee Casey, a columnist for the Rocky Mountain News, wrote on July 7, 1950, “These murals, as Mr. True paints them, will add dignity to our courts, and everyone knows that some of our courts need just that addition. They also will remind us of the early days of our jurisprudence, when weighty determinations were declared beneath the light of a coal oil lamp. . . . We need to respect our courts, if we are able to do so, and, before we respect, we must understand them. Mr. True’s murals will help towards achieving those ends. The two murals each measured eight by twelve feet.”

Miners Court, by Allen Tupper True. Photo credit: Marcia Ward, Imagemaker; courtesy of Victoria Tupper Kirby

B50 Note: Victoria Tupper Kirby is the granddaughter of Allen Tupper True and co-author with her mother and True’s daughter Jere True of the biography Allen Tupper True: An American Artist (available at Tattered Cover bookstores and on Amazon.com).

Colorado Artist Allen Tupper True (1881-1955) was a prolific painter, muralist, and illustrator whose work graces many buildings and monuments nationwide, including the state capitols of Colorado, Missouri, and Wyoming, as well as murals for the Civic Center and the Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company Building in Denver. Other True murals can be seen in the Brown Palace Hotel, Denver Civic Center Park, and the Colorado National Bank. He also designed the decoration and color schemes for the Boulder Dam power plant, Grand Coulee Dam, and the Shasta Dam, among others. His work is currently the subject of a wide ranging retrospective, Allen True’s West, presented by the Denver Art Museum, the Colorado Historical Society, and the Denver Public Library.