— by M Thornton

Buckfifty has become my biography, the story of Denver before I arrived, the story of Denver that I live, and the story that gives credence to the Denver of the future. Here’s one more tidbit, and I hope it connects me to you, to the place, to the community that is built on the stories, the gospel of its residents, because the stories are forever changing, thanks to the chroniclers and listeners.

The Jonas Brothers of Denver

Back in 1974, after a fleeting separation from a girlfriend in Chicago, the college girl I could have fun with, like hitchhiking downtown from college, before missing our post-college marriage, I moved back to Denver, and found a job near my apartment in Capitol Hill, at Jonas Brothers. I became a taxidermist apprentice, for six months, and told the students whom I teach now about that experience, and they all agreed that this was a story that would endure me to people everywhere — that’s probably because they have not dealt with wild animals in their lives, and neither had I. (I typically use this experience to shock high schoolers into imagining that at one time, in this far outpost of civilization, game trophies mattered.)

Jonas Brothers hired me because I responded to an ad in the paper, I passed a polygraph, and I was interested. The fur salon on the first floor of the building at 10th and Broadway featured a standing polar bear, one of the last to be legally hunted and stuffed. (This polar bear looked so much better than the shaggy ones I grew up seeing at the Denver Zoo.) It no longer could claw or kill, but the magnificence of this creature suggested a wild habitat, where people could nonetheless safely purchase real fur coats. This was my introduction to taxidermy.

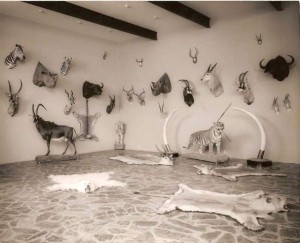

Once I started working around these people who devoted their lives to capturing the animal instinct, the bizarre nature of this old world craft never bothered me. The professional taxidermists who worked on the upper floors sculpted trophies made to mimic the wild haunts of the animals whose hides arrived through the alley door. Crates were unloaded, with hides that needed stretching, and skulls that required stripping in cauldrons of chlorine.

Once I started working around these people who devoted their lives to capturing the animal instinct, the bizarre nature of this old world craft never bothered me. The professional taxidermists who worked on the upper floors sculpted trophies made to mimic the wild haunts of the animals whose hides arrived through the alley door. Crates were unloaded, with hides that needed stretching, and skulls that required stripping in cauldrons of chlorine.

I would unpack an elephant foot, and over days of spraying it with water and tamping sand into it with a compactor, the foot would eventually regain its posture. We would add a circular plywood form to the inside, and top off the foot with a padded seat. An elephant foot stool. We would place the skulls of antelopes into a gigantic vat of bleach, where the final remnants of life would be stripped away, issuing ivory skulls a month later, to which we added missing teeth before we mounted them on a wood plaque. I learned about mixing epoxy glue to cement the dentures in skulls. I searched for missing incisors from drawers of teeth, catalogued by animal. My days were interesting indeed.

The taxidermists that worked at Jonas Brothers were the best of a dying breed, as they worked to make animals look as wild as possible, in their natural habitats. But safaris were on their way out, as wild game faced extinction, and so these craftsmen toiled as artists, scarcely making a living wage, without doing side work.

Did you know that fish lose their color once out of water? Fish trophies are painted to enact the real catch. Once while I was there, a hippo or rhino — they are both big game — died in one of the American zoos, and these artisans joyfully welcomed a new cast of the animal, that would better reflect how the beast would stand in nature. They would clothe it in hides from the next big game hunter. The taxidermists that I knew only watched PBS programming, Wild Kingdom at that time, constantly studying animals in their habitats, to better capture the life-like motions for their real-life resurrections.

Did you know that fish lose their color once out of water? Fish trophies are painted to enact the real catch. Once while I was there, a hippo or rhino — they are both big game — died in one of the American zoos, and these artisans joyfully welcomed a new cast of the animal, that would better reflect how the beast would stand in nature. They would clothe it in hides from the next big game hunter. The taxidermists that I knew only watched PBS programming, Wild Kingdom at that time, constantly studying animals in their habitats, to better capture the life-like motions for their real-life resurrections.

One time I brought my older sister through the gallery of animals to be shipped out. I thought that she would enjoy petting a tiger, but I’m not sure that she thought that I was anything but weird. I broke my ankle wrestling with a friend after a night of drinking, and another worker at Jonas fixed me up with a deer hide cover for my cast, that lasted the length of my working there. I didn’t see my future there, but those taxidermists impressed me no end for their love of animals, and their devotion to capturing beasts at their best.

I finally got a job on the Colorado and Southern railroad, as a gandy dancer on the track gang, yet another step back in time, another step back into a Denver that too often is ignored. The Jonas Brothers’ building still stands at 10th and Broadway, and members of the family still stuff game animals in Louisville, in a business that has been around since 1908. I suppose that “stuff” is not the proper word — maybe recreate and celebrate; and so we compose our legends of Denver.

B50 Note: According to this article published in People Magazine on April 19, 1976, Jonas Brothers was then “the largest taxidermy business in the world.” The article goes on to explain that once a year, at the “Hunter’s Dinner”, Jack Jonas would serve his guests a delicious and diverse menu, including a combination of gnu, elephant, warthog, hippopotamus, python, and other exotic delicacies.

Funny.